Màdera: Psicologia del profondo, pratiche filosofiche e spiritualità

Come si possano rispettare le diverse mentalità e convinzioni senza compromettere le proprie?

Romano Màdera è il fondatore dell’analisi biografica a orientamento filosofico (ABOF) e ha insegnato Filosofia Morale e Pratiche Filosofiche all’Università di Milano Bicocca.

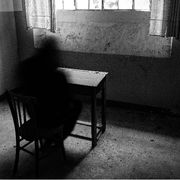

Un cambiamento si è verificato nei tipi comuni di patologie e nelle relazioni tra di esse, tutte ampiamente legate alla crisi nei quadri identitari, caratterizzata a sua volta da una difficoltà nel riconoscere i confini appropriati (confini tra sé e gli altri, confini tra sé e il mondo e i confini insiti nella propria personalità). Ciò ha portato alla diffusione di disturbi narcisistici, dipendenze e disturbi alimentari, attacchi di panico o, alternativamente, nel caso di un tentativo illusorio di mantenere il controllo, disturbo ossessivo-compulsivo e fobie. Anche i disturbi dell'umore sembrano essere correlati ad aspettative eccessive riguardo alle prestazioni, all'interno di un quadro complessivo confuso di ruoli sovrapposti e mal definiti. Ho affiancato l'analisi, le pratiche formative basate sulla filosofia come modo di vivere e la spiritualità in quello che ho designato "Analisi biografica a orientamento filosofico".

Tuttavia, la validità teorica del progetto dipende ancora dal fatto che affronti adeguatamente le questioni irrisolte poste dalla psicoanalisi, dalla pratica formativa e dall'accompagnamento spirituale, una volta che le giustificazioni scientiste, i modelli comparativi confutativi e le forme di esclusivismo religioso abbiano esaurito la loro funzione storica.

Quale quadro di significato permette di accompagnare diverse mentalità, scelte di ideali e posizioni etiche, condividendo la loro ricerca di espressione e riconoscimento - cioè, prendendosi cura delle loro divisioni - senza dover rinunciare alle proprie convinzioni o, al contrario, senza dover confutare le convinzioni dell'altro per evitare di essere ipocriti e manipolatori in modo collusivo?

Nel corso della mia carriera, questa domanda è sempre stata al centro dei miei tentativi di concettualizzare come l'analisi psicologica possa essere svolta in modo fattibile, rimanendo impegnata a rispettare il diritto dell'altro di pensare e attribuire valore in modo indipendente. La stessa domanda è inevitabilmente emersa fin dall'inizio del mio lavoro sul revival delle pratiche filosofiche come modo di vivere, dato che nell'insegnamento universitario una data scuola di pensiero è convenzionalmente messa in opposizione ad altre scuole di pensiero.

Oggi, c'è un enorme bisogno di cercare un significato personalizzato. È inevitabile: la maggior parte delle persone non si identifica più con la visione trasmessa loro dalla società e dalla loro famiglia di origine, perché la lunga storia del capitalismo moderno ha minato la stabilità sociale e culturale, dotando l'individuo della libertà di scegliere la propria visione del mondo, una libertà che è su una scala e assume forme senza precedenti. Ma poi, attribuire significato all'esistenza è la funzione chiave dell'animale culturale umano: l'immensa varietà delle differenze culturali parla della capacità dell'umanità di inventare modi di vivere per sé, adattandosi e trasformando ambienti ecologici altamente diversi, dai Boscimani del deserto del Kalahari agli Inuit nelle regioni artiche. Tuttavia, la distruzione dell'immagine del mondo ereditata dalle generazioni precedenti ha aperto un vortice infinito di possibilità. Nietzsche ha espresso perfettamente questo concetto ne La gaia scienza con la sua proclamazione metaforica che Dio era morto: alto e basso non esistono più, il giorno diventa notte e viceversa, il significato esplode in un numero infinito di configurazioni possibili, ma questa moltiplicazione esponenziale di significati alla fine distrugge la funzione selettiva che è un aspetto fondamentale del dare senso.

La psicopatologia, la malattia dell'anima che ha le sue radici nella nostra civiltà, è molto probabilmente l'espressione di questa crisi di significato, le cui riverberazioni si espandono verso l'esterno trasformandosi in una vasta gamma di sintomi. Tuttavia, evitare di pensare e sentire questa crisi è solo un'altra nevrosi difensiva, destinata a fallire a lungo termine.

Freud e la psicoanalisi avevano trovato una soluzione al problema, dichiarandosi parte della "concezione scientifica del mondo". Una risposta perfettamente moderna, che tuttavia soddisfaceva efficacemente - sebbene in forma surrogata - l'antica funzione di fornire un senso di appartenenza attraverso il riconoscimento del significato: non siamo alla deriva come l'ultimo uomo di Nietzsche, ma al contrario offriamo la soluzione razionale alla situazione drammatica di coloro che non sono più in grado di riconoscere un Dio unificante o un significato unificante; abbiamo la scienza. Questa convinzione aveva l'effetto collaterale chiave di proteggere la psicoanalisi dall'imbarazzo di essere paragonata alla "cura delle anime" religiosa, alla speculazione filosofica o addirittura allo spiritismo. Tuttavia, tutto ciò potrebbe essere considerato secondario rispetto al modo in cui la terapia psicoanalitica viene svolta e come i suoi risultati vengono concettualizzati. La posizione centrale freudiana è che l'ascolto deve essere liberato da qualsiasi legame ideologico o etico, oltre a quelli relativi al rapporto medico-paziente. La psicoanalisi non affronta idee o valori in quanto tali, tranne che per identificarne le origini nella famiglia e nell'inconscio. L'analista, quindi, non nasconde le sue convinzioni, ma come professionista impiega la sua scienza con l'obiettivo di portare alla guarigione. Così Freud poteva affermare che l'etica del paziente, sia che fosse un ladro o un gentiluomo, non era di alcuna importanza per il medico. Rimane ancora il dubbio che questa soluzione possa non essere appropriata, perché l'analista non è un medico: il suo strumento di lavoro è se stesso, comprese le sue convinzioni e valori: basta dire che le dinamiche di transfert e controtransfert sono lo strumento di scelta sia per l'osservazione che per la terapia.

Se, inoltre, la solidità della "concezione scientifica del mondo" - in realtà basata su fondamenta piuttosto fragili della filosofia positivistica - comincia a cedere, rivelando la sua indebita influenza sulle scienze moderne, allora la soluzione freudiana non regge più. E, di fatto, esiste una concezione scientifica del mondo? La fisica e la biologia sono segnate da una forte diversità, essendo entrambe molto diverse l'una dall'altra e ciascuna divisa in sottodiscipline specializzate che sono diversamente operative e producono diversi livelli di conoscenza: tutto ciò in realtà si lega alla nozione di una molteplicità di "concezioni del mondo". Certo, le discipline delle scienze naturali hanno alcune caratteristiche metodologiche comuni come l'accesso pubblico ai dati e alle procedure, il dibattito aperto sulle tecniche e sui risultati, la necessità di fornire prove per qualsiasi affermazione o deduzione fatta e, in molti casi, la necessità che gli esperimenti siano replicabili. Tuttavia, è chiaro che numerose concezioni del mondo, diverse filosofie e, oggi, anche molte religioni, possono considerarsi in linea con il modello delle scienze naturali, se non altro perché le scienze autolimitano il loro ambito di affidabilità a temi e metodi altamente specifici.

C

osì fino ad oggi la psicoanalisi ha subito il destino opposto a quello auspicato da Freud: il mondo delle scienze naturali è stato poco disposto ad accettarla, oggi ancora meno che in passato. Ciò è dovuto anche al fatto che la psicoanalisi soddisfa pochi o nessuno dei criteri di metodologia scientifica sopra menzionati. Inoltre non è riuscito nemmeno a sviluppare un linguaggio unificato: ci sono decine di scuole di psicoanalisi che competono tra loro per spiegare la stessa materia. Forse questo ostacolo potrebbe essere superato, se la questione non fosse anche a livello degli strumenti concettuali utilizzati, spesso difficilmente traducibili da un approccio all’altro.

Fin dai suoi esordi, la “scienza” della psiche si discostò in modo sconcertante dalle regole delle scienze naturali: Jung sosteneva che se la psicologia dovesse essere scientifica, dovrebbe cessare di definirsi una scienza, dato che la sua materia è e il suo principale strumento di ricerca sono la stessa cosa. Un paradosso evidente, come ci si potrebbe aspettare da un ricercatore che abbia deliberatamente adottato un linguaggio costantemente ambiguo! In realtà, Jung rimase fedele alla sua vocazione scientifica per quanto riguarda la posizione scelta di esaminare “come uno scienziato” – secondo i suoi termini “senza identificarsi né con il processo né con l’oggetto” – gli eventi psichici che aveva l’opportunità di osservare. o prendere parte a se stesso e agli altri.

La psicoanalisi, non potendo più rifugiarsi sotto l'ombrello della concezione scientifica del mondo, è così costretta a ritornare al suo dilemma originario, che nel frattempo si è fatto ancora più acuto: come è possibile incontrare gli altri, nell'integrità del loro mondo psichico, senza compromettere la propria autenticità? Come può esserci dialogo, scambio e aiuto tra mondi di percezioni, idee e valori diversi e, almeno a prima vista, in conflitto tra loro?

La psicoanalisi, non potendo più rifugiarsi sotto l'ombrello della concezione scientifica del mondo, è così costretta a ritornare al suo dilemma originario, che nel frattempo si è fatto ancora più acuto: come è possibile incontrare gli altri, nell'integrità del loro mondo psichico, senza compromettere la propria autenticità? Come può esserci dialogo, scambio e aiuto tra mondi di percezioni, idee e valori diversi e, almeno a prima vista, in conflitto tra loro?

Depht Psychology, Philosophical Practices and Spirituality

A shift has taken place in the common types of pathology and the relationships between them, all broadly linked to the crisis in identity frameworks, which in turn is characterized by a difficulty in recognizing appropriate boundaries (boundaries between self and others, boundaries between self and the world and the boundaries inbuilt in one’s own personality). This has led to the spread of narcissistic, addiction and eating disorders, panic attacks, or alternatively, in the case of an illusory attempt to remain in control, obsessive-compulsive disorder and phobias. Even mood disorders appear to be related to excessive expectations regarding performance, within a confused overall framework of overlapping and ill-defined roles.

I have placed analysis, formative practices based on philosophy as a way of life and spirituality side by side in what I have designated “Biographical analysis philosophically oriented”.

However, the theoretical validity of the project still hinges on whether it adequately addresses the unresolved issues posed by psychoanalysis, formative practice and spiritual accompaniment, once scientistic justifications, confutative models of comparison and forms of religious exclusivism have exhausted their historical function.

What framework of meaning enables one to accompany diverse mentalities, choices of ideals and ethical stances, sharing their quest for expression and recognition – that is to say, caring for their splits – without having to renounce one’s own beliefs, or on the contrary, without having to confute the other’s beliefs so as to avoid being hypocritical and collusively manipulative?

Throughout my career, this question has always been at the centre of my attempts to conceptualize how psychological analysis may feasibly be carried out while remaining committed to respecting the other’s right to think and attribute value independently. The selfsame question inevitably arose from the very outset of my work on reviving philosophical practices as a way of life, given that in university teaching a given school of thought is conventionally set up in opposition to other schools of thought.

Today, there is a massive need to search for personalized meaning. It is inevitably so: most people no longer identify with the vision transmitted to them by society and their family of origin, because the long history of modern capitalism has undermined social and cultural stability, endowing the individual with the freedom to choose his or her own world view, a freedom that is on a scale and takes forms without precedent. But then, attributing meaning to existence is the key function of the human cultural animal: the immense variety of cultural differences speaks for the capacity of humankind to invent ways of life for itself, adapting and transforming highly diverse ecological settings from the Bushmen of the Kalahari desert to the Inuit in the Artic regions. Nonetheless, the shattering of the image of the world that had been inherited from the previous generations has opened up an infinite vortex of possibilities. Nietzsche expressed this perfectly in The Gay Science with his metaphoric proclamation that God was dead: high and low no longer exist, day becomes night and vice versa, meaning explodes into an infinite number of possible configurations, but this exponential multiplication of meanings ultimately destroys the selective function that is a fundamental aspect of sense-making.

Psychopathology, the illness of the soul that has its roots in our civilization, is more than likely the expression of this crisis of meaning, the reverberations of which expand outwards transforming themselves into a vast range of symptoms. However avoiding thinking and feeling this crisis is only another defensive neurosis, destined to fail in the long term.

Freud and psychoanalysis had found a solution to the problem, by declaring themselves part of the “scientific world-conception”. A perfectly modern response, that nonetheless effectively fulfilled – albeit in surrogate form – the ancient function of providing a sense of belonging through the recognition of meaning: we are not adrift like Nietzsche’s last man, but on the contrary we offer the rational solution to the dramatic situation of those who are no longer able to recognize a unifying God, or a unifying meaning; we have science. This conviction had the key side effect of protecting psychoanalysis from the embarrassment of being likened to the religious “cure of souls”, philosophical speculation or even spiritualism. However all of this might equally be considered secondary to how psychoanalytical therapy is carried out and how its results are conceptualized. The core Freudian position is that listening must be freed of any ideological or ethical ties, other than those relating to the doctor-patient relationship. Psychoanalysis does not address ideas or values in their own right, aside from identifying their origins in the family and in the unconscious. The analyst therefore does not hide his beliefs, but as a professional deploys his science with the aim of bringing about healing. Thus Freud could claim that the ethics of the patient, whether a thief or a gentleman, were of no matter to the doctor. The doubt still remains that this solution may not be appropriate, because the analyst is not a doctor: his working tool is himself, including his beliefs and values: Suffice it to say that the dynamics of transference and counter transference are the instrument of choice for both observation and therapy. If, in addition, the solidity of the “scientific world-conception” – in reality based on the somewhat shaky foundations of positivistic philosophy – begins to give way, revealing its undue hold over the modern sciences, then the Freudian solution no longer stands up. And as a matter of fact, is there any such thing as a scientific conception of the world? Physics and biology are marked by strong diversity, being both greatly different to one another and each divided into specialized sub-disciplines that are differently operationalized and yield different levels of knowledge: all of which actually ties in with the notion of a multiplicity of “world-conceptions”. Of course the natural science disciplines do have some common methodological features such as public access to data and procedures, open debate on techniques and findings, the requirement to provide evidence for any claims or deductions made and, in many cases, the requirement for experiments to be replicable. Nonetheless, it is clear that numerous world-conceptions, several philosophies, and today, even many religions, may consider themselves in line with the natural science model, if for no other reason than that the sciences self-limit their range of reliability to highly specific topics and methods.

Thus to date, psychoanalysis has suffered the opposite fate to that aspired to by Freud: the world of the natural sciences has been little inclined to accept it, today even less so than in the past. This is also due to the fact that psychoanalysis meets few or none of the above-mentioned criteria for scientific methodology. Furthermore, it has not even successfully developed a unified language: there are dozens of schools of psychoanalysis that compete with one another to explain the same subject matter. Perhaps this obstacle could be overcome, if the issue were not also at the level of the conceptual instruments used, which are often difficult to translate from one approach to another.

From its very beginnings, the “science” of the psyche was disconcertingly out of line with the rules of the natural sciences: Jung argued that if psychology were to be scientific, it should cease to define itself as a science, given that its subject matter and its leading research instrument are one and the same. An evident paradox, as we might expect from a researcher who deliberately adopted consistently ambiguous language! In reality, Jung was faithful to his scientific calling in terms of his chosen stance of examining “as a scientist” – in his own terms “without identifying with either the process or the object” – the psychic events that he had the opportunity to observe or take part in, in himself and in others.

Thus psychoanalysis, no longer allowed to shelter under the umbrella of the scientific world-conception, is forced back to its original dilemma, which has meanwhile grown even more acute: how is it possible to encounter others, in the integrity of their psychic world, without compromising one’s own authenticity? How can there be dialogue, exchange and help between worlds of perceptions, ideas and values that are diverse and, at least at first sight, in conflict with one another?

© RIPRODUZIONE RISERVATA